Reach Across: Crossing social and cultural differences to proclaim the good news

Revs. Junius B. Dotson and Ron Bell, Jr. spoke at the Oct. 15 Reach! webinar about reaching across deep divides as we reach new people. Photo illustration by Karla Hovde.

This article is part of a series that will take place throughout 2020-21 in conjunction with the virtual Reach! webinar series. Learn about future Reach! webinars. Register for the Nov.12 webinar, which will focus on practical discipleship strategies for online ministries.

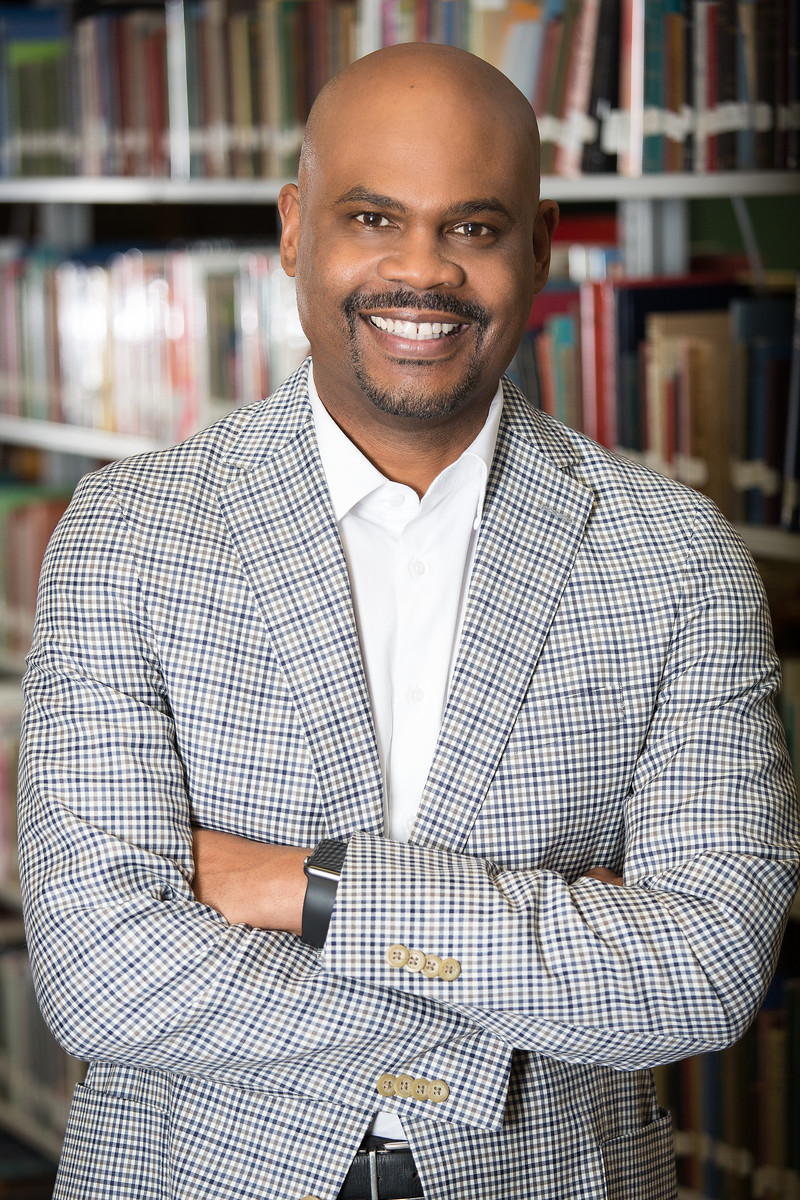

In order to make disciples today, we have to cross deep divides, Rev. Junius B. Dotson, general secretary of Discipleship Ministries for The United Methodist Church, told Dakotas-Minnesota Area church leaders at an Oct. 15 Reach! webinar.

Both Dotson and Rev. Dr. Ron Bell, Jr., who pastors Camphor Memorial UMC in St. Paul, shared their wisdom in a 90-minute presentation.

Dotson grounded his comments in currents events, such as the murder of George Floyd and the COVID-19 pandemic, both of which have exposed the deep racial injustice in the United States. He pointed out that these events compound the already difficult mission conditions we see in American society, with the rise of the “nones and dones”—those who claim no religious affiliation and consider the church to be irrelevant—and a climate of paralyzing political polarization.

“We have to minister in such a way that is culturally, socially, theologically relevant for such a time as this,” Dotson said. “This is the moment for the church to reclaim its prophetic witness.”

Rev. Junius B. Dotson is the general secretary of Discipleship Ministries for The United Methodist Church. Photo by Jack Harsh

What can the righteous do?

Dotson believes the question that faces us all now is: How do I hold on to my belief in the God of salvation and liberation in the face of the problems and contradictions that the world produces for my faith? In other words, “When the foundations are being destroyed, what can the righteous do?” (Psalm 11:3)

We may want to jump right into doing something when we see injustice, Dotson explained. But in order for our response to have integrity, we must acknowledge our past.

“In other words, history has to be more than a noble narrative; it has to be the truth we may not want to hear,” he said. This is true as we look at our history with slavery and racism, both in the U.S. and in The UMC.

“We have to hear the cries for justice if we are going to reach across deep divides,” Dotson said, especially as we see the rise of white supremacy locally and around the world. “Until we address this original sin of racism, we cannot adequately deal with the issues we confront as a church.”

The next step

Dotson pointed out that there are opportunities to connect with young people, many of whom are organizing around social justice issues and have a deep spiritual hunger but have been shunned from church institutions. The next step is for people in the church to engage these individuals in conversation and begin to form relationships and solve problems together.

Dotson pointed out that for many years, people have preached on racial reconciliation, but we see little change. Some Christians feel that if they treat people well, that’s enough. But if we want to make disciples for the transformation of the world, believers must be proactively anti-racist.

Rev. Ron Bell, Jr. added that we need to understand the distinction between an ally and an abolitionist. An ally is a fan of a movement, one who will buy the T-shirt but won’t take a hit for the team. An abolitionist is one who puts their reputation and their life on the line for the cause. When we think of being anti-racist, we need to think of being like Jesus.

“Jesus models that abolitionist mindset by putting his very life on the line for us,” said Bell.

In practical terms, each of us has to ask ourselves: Am I willing to stand with the people being oppressed; show up where the hurt is; study race issues; and finance anti-racist efforts? Am I willing to give up my comfort, my reputation, my legacy, to stand on the side of justice? It’s difficult, said Bell, but we can’t move forward until each of us is willing to do so.

Acknowledging trauma, starting the conversation

Rev. Dr. Ron Bell II, lead pastor at Camphor Memorial UMC, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Rev. Ron Bell, Jr. received the Denman Award for Reaching New People for his work at Camphor Memorial UMC in St. Paul at the 2018 Annual Conference.

Bell said each person in the U.S. is carrying a degree of racialized trauma. When we don’t deal with this racialized trauma, it continues to hurt us, gets passed down to the next generation, and becomes culture.

When you begin conversations around trauma and race, Bell said a good starting point is to ask: When did you know you were white? He said each of us, whatever our race, had a moment of realization about it. He can pinpoint the exact day when his two young children first knew that they were black.

The universal experience of carrying racialized trauma can only be a bridge to start conversations if we are willing to acknowledge the trauma and break through the shame that might keep us from being authentic, Bell said.

An exciting ministry opportunity in the midst of this pandemic is that different cultures and generations are able to engage in conversations via technology. Dotson encourages church leaders to access resources to facilitate small group conversations about race. He suggests that churches in different types of communities, such as an urban and a rural church, connect and start these relationship-building conversations.

Bell reminded attendees in rural or mostly white parts of the Dakotas-Minnesota Area that just as racialized trauma is not exclusive to African Americans, it’s also not exclusive to geography.

“We might use geography as a way to insulate ourselves against this conversation on race and racialized trauma,” but that doesn’t mean we aren’t carrying this trauma, said Bell. “You will discover that our perspectives are guided by our history, particularly those things that are subconscious, that have become latent, that have become culture, because they have never been resolved. Each of us has to do that work to see how we might heal and go forward together.”

The good thing is that there are opportunities for us to do just that. “We can be consumed with the darkness we see, or we can go light a candle,” said Bell.