National Creation Care Summit sparks learning, conversation, action

Creation Care Summit attendees / Photos courtesy of Revs. Nancy Victorin-Vangerud and Susan Mullin.

More than 100 United Methodists from 17 states and the Philippines gathered in Minnesota last week to discuss environmental stewardship and explore specific ways in which they are called to care for the planet.

The Creation Care Summit is an annual event for clergy and laity, and it moves to a different city each year. The 2018 gathering took place July 26-29 at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota. Attendees listened to a panel discussion on what they’re called to offer the world at this moment, heard from Dakotas-Minnesota Area Bishop Bruce R. Ough and Jim Bear Jacobs of the Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation, and engaged in action planning around topics they are passionate about.

“I hope attendees left energized, hopeful, and with a direction for action,” said Rev. Susan Mullin, a deacon who serves Faith UMC in St. Anthony, Minnesota and one of the organizers of the summit. “My dream is that we come to realize as a church that our theology includes caring for the earth and the people of the earth. We’ve come to understand environmental justice as issues that are peripheral to who we are as Christians—but they are at the heart of who we are. I think when we really know that and claim it, we’ll see a change.”

Workshop at Frogtown Farm in St. Paul, MN.

In a thought-provoking sermon during worship, Bishop Ough talked about how we are co-creators with God, who has given us stewardship authority and power. We have the power to destroy the life of other living things, to clone other living creatures, to start wars, to make peace, to harness the energy of the atom and the sun, to pollute creation, to hoard the resources God has given us, to be generous with what God has given us, he said. “As you give leadership to a creation care movement, I urge you to wrestle with the central question of the creation story: ‘What will you do with your blessing of power?’’’

The next day, Jacobs—parish pastor at Church of All Nations in Columbia Heights, Minnesota—made a case for the second chapter of Genesis being the story of a midwife delivering a baby. Pulling life from the body of the earth is not unlike pulling a child from the womb of his or her mother, he pointed out. We sometimes think the Industrial Revolution is to blame for the creation care crisis, he said, but it’s actually patriarchy—thinking of the earth as an “it” instead of a “her.” Earth is one of our relations, he told attendees, and our actions should reflect that.

Attendee Debi VanDenBoom, a student at Garrett Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois, and a member of the Wisconsin Conference, said creation care is near and dear to her heart, but she’s never preached on it before. She appreciated the opportunity to hear from the presenters and see them demonstrate what it might look like to do just that, and she’s committed to addressing creation care from the pulpit going forward.

Field trip to sacred "Red Rock" in Newport, Minnesota.

“I will definitely engage my preaching differently,” she said. “Since I hadn’t had anyone model it, wasn’t something I put at the forefront as far as importance…but if we continue to harm Mother Earth and our resources, that harms all of us. I can’t change people. But I can present in a prophetic voice the harm that is being done that we tolerate. People can make a difference if they choose.”

Much of the third day of the conference was spent in what Mullin describes as “transformative action planning.” Individuals wrote down issues or questions they wanted to discuss, and others joined them to brainstorm about topics of common interest. It was a way to network, share ideas, build partnerships, and agree on next steps.

That designated time for open-ended conversation was one of the things Bob Downs appreciated most about the conference—and what made it different from others he’s attended. A retired member of Christ UMC in Kettering, Ohio, Downs spent most of the action-planning sessions talking with others about creating a course of study for small groups to use within local churches. They envision something along the lines of a Disciple Bible study but one that focuses on education around environmental issues and exercises that help people explore how to address them in their own context.

“God expects us to be good stewards of the creation He gave us,” said Downs. “Climate change is a real threat to the whole planet…Church is a community that needs to respond. We’re dealing with a moral issue, not a scientific issue that scientists alone can address. It requires people to actually respond and make some changes in the way they live.”

Attendees were invited to participate in a variety of topical workshops and field trips throughout the four days of the summit. Field trips took them to one of the largest urban farms in the country and to see and learn about the history of a granite boulder located on the grounds of Newport UMC that’s considered a sacred object to the Dakota. The Minnesota Conference is making plans to return the “Red Rock” to the Dakota as an act of healing and reconciliation. Workshops included topics such as strategies for a waste-free workplace and home; the intersection between faith community, environmentalism, and environmental justice; ways to pursue solar energy; and how to have non-polarizing conversations about climate change.

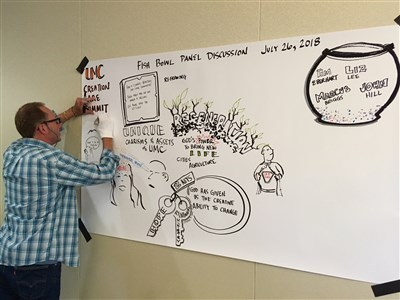

Graphic recorder Trey Everett captured the ideas presented.

“There will be great action that comes out of this, I’m quite confident,” said Cathy Velasquez Eberhart, a member of Prospect Park UMC in Minneapolis, Minnesota and one of the organizers of the summit. “I hope attendees left with a sense that each one of us has our unique role to play and that we’re not alone, and that they will go home with energy and clarity around their work, knowing that they have partners coming alongside them.”

Eberhart stresses that everyone is needed to address the environmental concerns facing our world, and The United Methodist Church has an opportunity and an obligation to be part of that change.

“It’s part of the mission of The United Methodist Church to be out there transforming the world,” she said. “This is a part of that. We really need people in every annual conference and in as many local churches as possible bringing their skills to this work, whether they’re teachers or farmers or curriculum writers or worship leaders. My dream would be to get to a point where we’re helping society make a shift.”