Remembering Martin Luther King Jr. in a season of violence and racism

Bishop Ken Carter, president, Council of Bishops. UMC file photo.

I was 11 years old when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. Some people can remember where they were when President John Kennedy was assassinated.

I grew up in Columbus, Georgia, the midpoint between Montgomery, Alabama, where King served Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, his first pastorate, and Atlanta, where he was born and where he returned after Montgomery.

Upon learning of the death of Martin Luther King, the response was one of ambivalence among many white people who were not enthusiastic admirers of King. In the months ahead, and especially the summer, the response would become one of rage, bringing early curfews, and, for a young boy, fear and chaos.

Years later, I was required to read one of King’s books in a divinity school class, a slim volume entitled, “Why We Can’t Wait.”

In its pages, I encountered a different Martin Luther King than I had expected, or perhaps I was different. King had grown up in an enclave of middle-class black people in a very segregated section of Atlanta. He had the advantages within this community of heritage, personal charisma, rhetorical greatness, and a superior mind. All of these gifts came together in him. He had both a national forum, among black people and white people. He had had something to say, and he said it.

King had wrestled with the implications of the black struggle - he met Rosa Parks, who refused to sit in the back of the bus in that first pastorate, in Montgomery - and he came out on the side of non-violence.

He was pursued by the FBI and local sheriffs, ridiculed by those who wanted him to retaliate and dismissed by Malcolm X as not being tough enough. He was committed to non-violence, which he saw as an implication of a greater reality, the love of God and neighbor and the call to follow Jesus.

King was committed to non-violence because he had been given an enlarged vision of the Kingdom of God, which he described in his early sermons as the beloved community. He understood that black people and white people in this nation (and in the church) had a common destiny.

Martin Luther King, like each of us and like so many of the biblical characters, was flawed and human. But he perceived a vision for the church and the nation, and he was willing to work and to suffer toward that end. In a speech he made the point clear:

“The cross we bear precedes the crown we wear. To be a Christian, one must take up his cross, with all its difficulties and agonizing and tension-packed content, and carry it until that very cross leaves its marks upon us and redeems us to that more excellent way which comes only through suffering.”

In the gospel story, John the Baptist greets Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world (John 1). Most likely, Jesus is linked in this passage to the suffering servant of Isaiah, who was compared “to a lamb led to the slaughter” (Isaiah 53).

God’s spirit had been placed upon the suffering servant, who would bring forth justice to the nation (42. 1), and who would represent the mission of Israel not only to the tribes of Jacob but who also would call them forth as a light to the nations (49. 6), that the salvation of God might reach to the ends of the earth.

We know that Jesus interpreted his mission in light of these suffering servant passages of Isaiah. Jesus is the suffering servant for the world, the sacrificial savior, the bearer of God’s universal offer of salvation, who ushers in a new age of righteousness, and takes upon himself our sin and guilt.

Jesus comes to make all things new. Jesus comes to be our peace. Jesus is the embodiment of the Kingdom of God in our world.

What might all of this mean for those of us who live in an increasingly violent and polarized world, where the Lion and Lamb do not lie down together?

As the scripture says, this will be a sign for you.

In my seven years of ministry in the Florida area, we have witnessed the murder of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, the massacre of 50 in the Pulse shootings in Orlando, and the deaths of 17 students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland.

Last week I toured the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial, which documents the history of lynchings related to racist terrorism in our nation’s history. Twenty persons were lynched in Polk County, where I live. The Museum and Memorial compellingly connect lynching and capital punishment, slavery, segregation, and mass incarceration.

The crisis of the present moment leads us to a series of questions.

Are we not our brother's keeper, which means not only that we care for the most disturbed among us (which would mean more treatment for the mentally ill, not less) but that we hold them accountable, which means we do not allow an ordinary citizen to purchase a weapon that can kill a dozen people in a matter of seconds?

Are we on our own, or can we recognize the mentally ill flooding our streets, our shelters, some returning from war, some long-term unemployed? Do we recognize the cost of the violence that staying on the sidelines of all of this entails for us?

And can we go deeper into it all? Can we not agree, at a more fundamental level, that the way of Jesus is non-violent, can we not remember in his sermon on the mount that he blessed the peacemakers and called them children of God?

Can we not recall, going back further, that he did not retaliate against his enemies but saw in Isaiah's prophecy a different and higher way, through suffering that was redemptive? He is the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world.

And can we live into the callings given in our baptisms, that God shows no partiality, that white supremacy is a sin against the truth of a gospel that Jesus has died for all, a sin that results in present realities of mass incarceration and profiling of young black males?

The gospel is radical, displaying the extremes to which God would go to save you and me.

I am reminded that, in his lifetime, Martin Luther King was regarded as an agitator, a troublemaker, an extremist. In his Letter From the Birmingham Jail, he offered this response:

“Though I was initially disappointed in being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter, I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love? “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them that despitefully use you and persecute you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice? Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream? Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel? “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.”

"Was not Martin Luther an extremist? “Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise, God help me.” And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

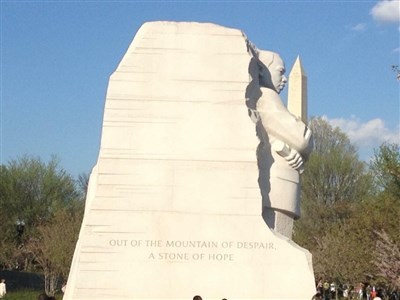

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo by Maidstone Mulenga, Council of Bishops.

Interestingly, Martin Luther King, Jr. was actually born as Michael Lewis King. His father was the pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta and after several years of ministry, which included helping to keep the church open during the Depression, the church as a reward sent him one summer to Israel, the Holy Land, and Germany, the home of the Reformation.

Upon his return, he changed his name, and his son’s name from Michael Luther King, Sr. and Jr. to Martin Luther King, and he re-baptized his son.

Martin would grow into this name. Like the reformers before him, he rediscovered something that had been hidden, suppressed, ignored, even in the Bible Belt. And he did this primarily as a preacher of the gospel.

He once said, of himself, “In my essence, I am a Baptist preacher. This is my being and my heritage, for I am the son of a Baptist preacher, the grandson of a Baptist preacher, and the great-grandson of a Baptist preacher.”

He was a radical reformer in the sense that he went back to the roots, the scriptures, the prophets, the Sermon On The Mount, and our nation’s founding documents. He held them up for us and would not let us turn our eyes away.

In a meeting with students in Albany, Georgia, early in his ministry, he listened as a young woman student opened the worship service with prayer. There was a continuing refrain in her words: “I have a dream, I have a dream, I have a dream.”

Like all preachers, King would borrow those words and make them his own, and our own. And so, when he stood up before the nation to speak, and announced, “I have a dream,” he was tapping into the deep undercurrent in the hearts and minds of many, many people, who longed for a better and different world, and who were willing to suffer toward that end.

I have been to Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, again most recently last week. I have touched Dr. King’s study desk and paused to pray in the sanctuary. A former pastor of that church, Rev. Michael Thurman, was a close friend and valued colleague.

Dexter is a block on the main street leading to the state capitol building, formerly the capital of the Confederacy. That would be prime real estate in most cities until one learns that it was a slave pen before it was a sanctuary.

That is a vivid image of the gospel that Martin came to announce. Jesus comes to save us, to redeem us, to set us free. That is an extreme act of an extremist God.

And if we are his people, we are called to be extremists in a violent and polarized world, to envision a kingdom that is not of this world, and yet to work to change the world, even as we pray, “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

At his core, in his essence, Martin was a preacher of the gospel: “Behold the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.”

And yet he wanted us to respond to the gospel, and so he asked and asks the question echoed in the hymn, a hymn that would have been sung in many of the services that he led, “Must Jesus bear the cross alone?” They understood the cross as pain, injustice, frustration, despair, suffering---“must Jesus bear the cross alone, and all the world go free?”

No.

“There’s a cross for everyone, and there’s a cross for me.”

Sources: Richard Lischer, The Preacher King. “Must Jesus Bear The Cross Alone,” United Methodist Hymnal; Martin Luther King, Jr., Why We Can’t Wait.